|

| http://www.blogcatalog.com/ |

Kids often see symbolism as something arbitrarily assigned to books they have to pretend to read in order to pass, by people with no real-world skill sets. "Right, we get the rose in The Scarlet Letter and the role of nature in Macbeth. We get it because we skimmed SparkNotes before class. Whatever."

And it isn't just students who have this problem. Consider this article in the Atlantic, proffered by another friend who, as the wing historian, shared a hallway with me at Aviano Air Base. The piece discusses Brad Paisley's relationship with the widely recognized Confederate battle flag. My friend passed it along the day I published It's My Right! and it comments on the connection between Paisley, the Confederate flag, and that post's element of offense giving and taking.

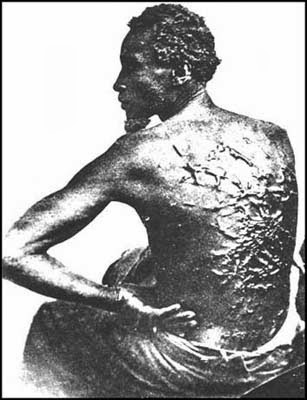

Coates, the writer of the Atlantic piece, does a great job explicating the flag's symbolism to modern African-Americans, whose North American history as an enslaved group makes the flag particularly repugnant. This is the kind of strength many of my non-African-American students don't grasp. "It's just a flag. Why are people getting worked up?" And yet these same students wear other symbols, often eager to get them permanently inked on their skins. It's important to get them to understand that everyone is moved by symbols because they need to see how they themselves are moved and often manipulated in order to understand exactly why "just a flag" can stir deadly passions.

Coates, the writer of the Atlantic piece, does a great job explicating the flag's symbolism to modern African-Americans, whose North American history as an enslaved group makes the flag particularly repugnant. This is the kind of strength many of my non-African-American students don't grasp. "It's just a flag. Why are people getting worked up?" And yet these same students wear other symbols, often eager to get them permanently inked on their skins. It's important to get them to understand that everyone is moved by symbols because they need to see how they themselves are moved and often manipulated in order to understand exactly why "just a flag" can stir deadly passions.This general blindness, a meta-emotional deficit if you will, causes us to see symbols only through the lens of our own experience and accept our reaction to the symbol as normal and natural and others' reactions, if those reactions don't coincide with ours, as trivial or ridiculous.

This alternative opinion of the Brad Paisley question opposes Coates' view and illustrates how those who embrace the flag see it.

Both are correct, at least from the perspective of decoding symbols. Both sides view the flag in their cultural context and, while recognizing opposing points view, are generally dismissive. How you view the Confederate flag, a priori, will make you nod your head in agreement with one or the other. Confirmation bias ensures that.

However, it isn't enough to recognize that we recognize others' bias. It isn't even enough that we recognize our own bias. If we stop there we risk stalling at a shoulder shrug and sleeping forever between the sheets of moral relativism. We still have to take action in the world, the best path we can discern. We have to judge and act on those judgements, to realize our human failings and prejudices and to move beyond them the best we can.

There is no moral ambiguity in the case of the Confederate flag. It so strongly represents verifiable and widespread oppression and murder to such a large group of people that to argue that admittedly, the flag does represent a bad idea, but it represents honorable qualities as well, is disingenuous. It is like asking a judge to grant mercy to a prolific serial rapist and killer of many because he was also a good father to a few. As a nation we have long agreed that enslaving and oppressing people is clearly wrong, whether you lived in antebellum Alabama or Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, whether you are selling human beings or cutting off little girls' noses.

What then, can be gleaned from this exercise? If you didn't listen in my class, you will walk away shrugging that symbols are there to keep English teachers in chicken and rice and will cheer when your team wins and be baffled or angry when other people bitch about your team's mascot. And you won't be alone.

3 comments:

Alright Chief I want to ponder this. You say, "There is no moral ambiguity in the case of the Confederate flag. It so strongly represents verifiable and widespread oppression and murder to such a large group of people that to argue that admittedly, the flag does represent a bad idea, but it represents honorable qualities as well, is disingenuous." Okay, but one could say the same thing about the U.S. flag that flew so proudly as it was carried on U.S. Army missions to massacre Native American tribes throughout the country and to usher them into areas of control. One could even say the same thing about the Union Jack during the Revolutionary War or even during Britain's conquering throughout the world and the death and destruction of indigenous tribes they left behind. The point I feel is that too much emphasis is put on the Battle Flag of Northern Virginia when I could pick any flag of any country and say the same thing you said about the Confederates. Now don't get me wrong, I love this country more than most and understand history is history for us to learn from, but don't demonize only the part you don't like.

I have often advocated the flying of the official flag of the Confederacy on state grounds and monuments where the battle flag is now flown. Given the lack of historical knowledge by the average American, few would realize what they were looking at and fewer would even care other than those who follow Al Sharpton. States like Georgia, which incorporate the battle flag within their state flags could change to the official flag and be hailed for the move until some intern at one of the news networks figures it out.

You make a good point, and as individuals we do have to decide how much we are willing to offend. It is true that oppression has occurred under the American flag. It waved over a century of Manifest Destiny, as you point out. No symbol is unstained, especially national symbols.

Your comment about demonizing the parts we don't like reinforces my point regarding how we perceive symbols. Perhaps as a nation we can admit and come to terms with the role our current symbol has played and word to rehabilitate that symbol. The Confederate battle flag, however, remains frozen in time. It can never be rehabilitated since the nation it symbolized is gone. Some US military units used to take pride in their flying of the Confederate flag, but have, since the end of WWII, pulled down and eliminated their association with it.

It is the symbol of a failed state whose enslavement of the ancestors of a wide swath of our current citizenry that at the very least, that part needs to be recognized by those who choose to wave the symbol. If those who wave it decide that they do indeed want to offend that group, it if of course their right, but they should not attempt to defend it by saying they only recognize its noble qualities and can't understand what all the fuss is about. I don't want to go to Europe n this post, but there is an obvious analog from the last century here. A failed state, a brutalized people, and a few in modern society who wish to wave the symbol of the failed state, claiming its honorable qualities.

Post a Comment